I did a little sightseeing yesterday, joining two friends on a trip to the Seodaemun Prison History Hall (서대문형무소 역사관) near Dongnimmun (독립문) station and inside the Independence Park. The museum is dedicated to recording Japanese torture and cruelty towards the “patriotic ancestors” of the independence movement. The prison in question, built by the Japanese just prior to annexation, continued to be used well into the postwar period, but it is now overwhelmingly used as a symbol of colonial atrocities and you will find no mention of its postwar legacy. I think many of my observations about the place have been shared by others, including some of the comments made by an Adam Bohnet here.

Technorati Tags: Korea

The museum is cheap to enter (1,500 for adults) and begins in a white museum building where they get you warmed up. Inside, the first floor has exhibit boards about some 44 independence activists from the March 1st movement (including some women) and describes their fate.

The museum route leads on to the basement where the main thrust of the museum’s narrative is found. The visitor is assaulted by the sounds of screaming prisoners and the evil chuckles and yells of Japanese prison guards. In the dimly lit corridors with blue and red lighting at strange angles emerging from the exhibits, you are presented with scenes of disgusting torture and pitiful imprisonment. The exhibit captions abound with strong adjectives emphasizing the suffering and sacrifice of the patriotic ancestors and the diabolic nature of their Japanese oppressors. Exhibit walls are splattered with patriotic blood and we become witness to sexual torture, pins stabbed in nails, brutal beatings, and one exhibit which simply has a Japanese guard model leisurely watching the exhibit of torture on the other side of the corridor with a sadistic expression on his face.

Having now demonstrated the horrors of oppression, the narrative moves, much like the war memorial museum south of Seoul does, to the enraged response of the Korean nation. The second floor gives some historical background on the March 1st movement, and traces the nationalist movement in Korea. There is a nicely done combined movie-doll presentation (“Magic Vision”) simulating a patriotic bomb throwing assassination of some Japanese by a Korean patriot. The arrogant and laughing Japanese men and women who emerge from their carriage waving a Japanese flag are consumed in the flames of the bomb and fall to the ground dead or wounded. Narrated in solemn and patriotic style, the presentation amounts to a wonderful celebration of terrorist violence for the noble cause of national liberty and independence.

The second floor also traces the prison’s history. We find examples abounding here of an interesting issue in the historiography of nations who have experience colonialism. There is a tendency to portray all which is evil and objectionable about modernity as having not been a feature of the modern state, but the cruel and determined act of the colonial oppressor. For example, note this passage found on one caption talking about the emergence of the modern prison in colonial Korea:

Traditionally, Korean prisons were used to house unconvicted prisoners before executing their sentence, and the scale of prisons was not required to be large, under the [Confucian] ideology of “Control by Virtue,” and “Benevolent Government”; the manifestation of this philosophy was to build prisons, but keep them empty. However, the invasion of Japan totally shook the root of this tradition. Japan constructed a lot of prisons all over the country to oppress the Anti-Japanese independence movement, and inflicted ruthless torture and imprisonment…”

Notice what is being said here. There is the explicit contrast between the virtuous Confucian “rule by virtue” where prisons are built but kept empty, and the specific act of the Japanese to oppress the Koreans, “shake the root of this tradition” and ruthlessly torture prisoners.

As always, it isn’t so much the content, but what is left out. The pre-modern forms of punishment in Korea (See Shaw, William Legal Norms in a Confucian State. Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies University of California, Berkeley, 1981) were highly developed, along with its legal system, but were brutally violent as well. Torture was completely normal part of the extraction of confessions by criminals, and it was also common to torture witnesses who weren’t even accused of anything. Having said that, pre-modern punishment doesn’t always come out so badly when you take a closer look at things and compared with modern times when we shift from punishment and exhibition of the body to confinement and conformity of the mind (Foucault’s Discipline and Punish gave birth to a whole slew of approaches based on this). Daniel Botsman has written a fascinating English account contrasting the pre-modern and modern forms of punishment in Japan with his new Punishment and Power in the Making of Modern Japan which deals with the more difficult issues at work here.

Perhaps more importantly, the other thing completely missing from this floor is an answer to the question of, “What happened after independence in 1945?” Without being posed, the assumption is perhaps made by many, especially younger visitors, that when the Japanese went home, oppressive prisons, torture, and executions became a thing of the past. This of course, is tragically not the case.

Postwar Korea boasts a long and ignoble history of torture, unjust imprisonment, political oppression, and dictatorship which stretches decades into the postwar period, and I would not be at all surprised if this prison had business as usual in the postwar period. In fact, I’m sure we could find a few prisons and jails in Korea where we could construct equally elaborate exhibits focused only on the history of atrocities committed by Korean guards against left-wing or democratic protesters in the postwar period alone.

This is not the story being told here. Like most nationalist narratives, the emphasis is squarely on the oppression that they committed against us. It is not as interesting or urgently pressing that we teach our people about the atrocities committed by us against us. That is not to say that these museums and books cannot be found, but the stain they make on national history is such that it is far more important for “patriots” to concentrate on the crimes of the invader, committed by those who do not share the same blood.

Note this interesting comment found on the blog of some student studying in Seoul:

While we were touring [the prison museum I] asked Prof Lee if she is having fun (because she looked bored), she replies, i only have fun if there are japanese students with me, then i show them what they did to us, no one hurt my korean pride…no one”

To me, this is perfectly representative of the tragedy that is national history. This teacher is apparently not interested in teaching about the atrocities of the museum, unless it is an opportunity to tell the Japanese about what they had done. To begin with, we can note that the Japanese she takes to the museum haven’t done anything of the sort.

This example is extreme, I think most teachers would want to teach Koreans about what the Japanese had done to us and that is clearly what the emphasis is on. However, because of the overwhelming heavy shadow of national history, it doesn’t seem to occur to anyone that we might want to tell the story of torture, execution, massive punitive and reformatory confinement, and state oppression in a somewhat broader way. There is lots of room for colonial oppression, Japanese and atrocities in such a story. However, there would also be room in such a story for comparison with pre-modern crime and punishment, and especially for the continuity which exists between colonial oppression and the shameful history of torture and repression in the postwar period. Alas, this is perhaps too much to wish for in a place called Independence Park.

I was a little surprised to see that the majority of other visitors buzzing around us during our visit were elementary school children. Children under 6 are free, and there are discount tickets for teenagers and there is even a separate category for children aged 7-12. They seem little disturbed at the screams, the blood, and some diligently took notes on the captions describing the brutality of the Japanese prison guards. I was impressed by their English too. When Craig was watching a simulation of some particularly nasty torture, a young girl approached him and said in almost perfectly pronounced English, “Excuse me, may I watch it too?”

I was also surprised at how much the museum caters to younger visitors, providing torture boxes that you can enter, and exhibits only visible by crawling. There was also an interactive execution chamber. You sit on top of the chair that will drop a condemned prisoner for hanging and can hear the Japanese judges pronounce the sentence as the ground under the chair suddenly drops slightly.

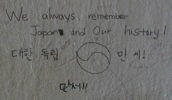

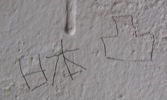

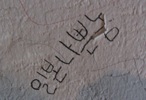

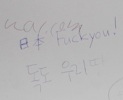

Despite its claim to want to have visitors be overwhelmed with respect for the patriotic ancestors who sacrificed themselves for the independence movement, above all, this museum is about cultivating anger and hatred. At that task, it succeeds incredibly well. The walls of the museum, especially in the basement torture exhibits are covered with anti-Japanese graffiti and I heard both teachers and students making all sorts of comments about Japan. Below are a few pictures of the graffiti found everywhere. The most common graffiti throughout was the use of a symbol which looks like the Chinese character for “convex” (凸). Craig and I could only conclude that this character must stand in for some kind of insult.

Um, seriously, I do believe you know what the “凸” stands for…

Um, if not, I’ll be suprised, cause it means that that symbol must have been made by the Koreans, not an “imported” symbol. Isn’t it used in the States also? (No?)

No I honestly haven’t seen that before either in the US or in Japan (although in the latter case, it may be my own ignorance…) Perhaps you can tell me what it means when we have lunch!

(凸) is the Korean netizen’s way of giving someone the “bird” or the middle finger on-line….

In your photos, IMG_0080.jpg = IMG_0076.jpg

Thanks! Figured it was something like that…

Yep, It actually was a little bit obvious…

Hmmm… sounds like an ultra-nationalist version of the London Dungeon (very tacky tourist attraction, sort of like Madame Toussauds with added torture).

I lived a few minutes away from Sôdaemun Prison and always meant to go there but never did. Now I’m quite glad.

Keep up the excellent Korean posts Muninn. (화이팅!)

Actually, that symbol is a real kanji in Japanese, meaning convex, also in combination with something else to indicate unevenness in a surface. I knew about those, and in looking it up in my 国語 dictionary I also discovered it can mean the furrowing of the brow.

Yeah, it’s a real kanji, but in this context it does mean the middle finger. You see it in emoticons like 凸(-.-)凸

楽しそうな博物館ですね。

凸 = tu in chinese. A ‘bulge’ if you will.

the huge difference between the japanese keeping korean catives here and the koreans keeping captives here is reason. the reason the japanese captured koreans were to colonize them. any koreans who refused to submit to learning japanese language and taking japanese last names and what not were captured and tortured. where as the koreans who captured koreans were people who commited crimes, etc. also the museum doesn’t write of some of the things japanese did to koreans outside the prison while trying to colonize it. this includes slicing people open while still alive to learn about the body. and trying different drugs and medications and using koreans as labrats. thats one of the reasons they were so good at torture and curing — due to these experimentations.

Um, I think you have got your facts just a tad exaggerated but certainly there is no doubt the Japanese wanted to “colonize” the Koreans. That often happens in colonies, I’m afraid.

I have confirmed that Seodaemun continued long after the colonial period, was the site of more torture, more executions, and was far more crowded with prisoners after 1945 than before. I have come across several newspaper articles from the early postwar period decrying the horrible conditions in the prison. Most of the prisoners were not regular criminals, and I don’t know the statistics for the Japanese colonial period, but suspected leftists.

There are unique problems to imperialism that are worth discussing, but I think that if the museum wants to talk about the institution’s history of torture and death – tell the whole story that includes the horrors of the postwar period. No one has killed more Koreans in the 20th century than the Koreans and that should be studied side by side and with great care alongside the darker aspects of colonial rule by the Japanese. Oh wait, how could I forget, I guess the US probably killed the most in their bombing campaigns.

The full history of the horrors and evolution of Seodaemun Prison is a PhD thesis waiting to be written…

Now THAT IS what I deem an insightful take on things. What I would advise though is talking to other people actively involved in the scene and bring to light any conflicting points of view and then update your site or create a new post for us to stew over. Hopefully you’ll take my advice, I’m looking forward to it! Try to cover off on some graffiti characters as well if possible, they’re quite popular at the moment.

http://adrworks.ca/?p=4